Imaginary Economies: The Case of the 3D Printer

Text von Jens Schröter in ökonomischer Fachzeitschrift!

In the call for this special issue for the EAEPE Journal we can find the word ‘scenario’. The question is, if the authors can imagine scenarios in which “potential strategies for the appropriation of existing capitalist infrastructures […] in order to provoke the emergence of post-capitalist infrastructures” can be described. Obviously, the call verges on the border of science fiction – and this is not a bad thing. Diverse strands of media studies and science and technology studies[1] have shown that not only the development of science and (media) technology is deeply interwoven in social imaginaries about possible outcomes and their implicated futures, but there is a whole theoretical tradition in which societies as such are fundamentally constituted by imaginary relations.[2] But in all these discussions, one notion very seldom appears: that of an ‘imaginary economy’, meaning a collectively held system of more or less vague or detailed ideas, what an economy is, how it works and how it should be.[3]

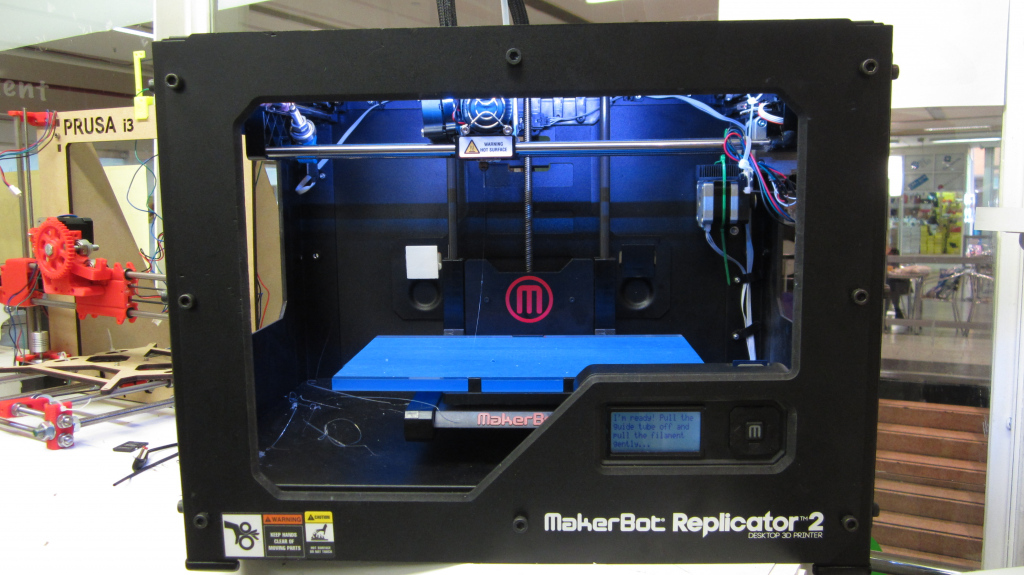

Obviously here a gigantic research field opens up (think alone of the traces of imaginary economics in science fiction[4]) – so in the proposed paper only one type of ‘imaginary economy’ can be analyzed: It is the field that formed recently around the proposed usages and functions of 3D-printing. In diverse publications[5] the 3D-printer operates as a technology that seems to open up a post-capitalist future – and thereby it is directly connected to the highly imaginary ‘replicator’ from Star Trek. In these scenarios a localized omnipotent production – a post-scarcity scenario – overcomes by itself capitalism: But symptomatically enough, questions of work, environment and planetary computation are (mostly) absent from these scenarios. Who owns the templates for producing goods with 3D-printers? What about the energy supply? In a critical and symptomatic reading, this imaginary economy, very present in a plethora of discourses nowadays, is deconstructed and possible implications for a post-capitalist construction are discussed.

[1] Cf. Schröter (2004); Kirby (2010); Jasanoff & Kim (2015); McNeil et al. (2017).

[2] Cf. Castoriadis (1990).

[3] Especially in the future; but see the somewhat different usage in Fabbri (2018). Jessop (2013) has developed a very similar notion of ‘economic imaginaries’, which he defines (p. 236) as a “semiotic ensemble that frames individual subjects’ lived experience of an inordinately complex world and/or guides collective calculation about that world.” He argues, that “totality of economic activities is so unstructured and complex, it cannot be an object of effective calculation, management, governance, or guidance. Such practices are always oriented to ‘imagined economies’.” Therefore: “Economic imaginaries have a crucial constitutive role here in so far as they identify, privilege and seek to stabilize some economic activities from the totality of economic relations. They give meaning and shape thereby to the ‘economic’ field but are always selectively defined.” He makes a detailed analysis of the imaginaries that accompanied the crisis after 2008. Theoretically I completely agree with Jessop, the main difference is, that he doesn’t read popular discourses, like e.g. science fiction, although their popularity heightens the relevance of the imaginaries produced there. Jessop bases his argument on the interesting study of Taylor (2004), see there especially chapter 5 on the economy as modern social imaginary.

[4] Cf. Davies (2018) and Schlemm (2019). See also the interesting website on “Economic Science Fiction & Fantasy”: http://www.economicsff.com/.

[5] For example Eversmann (2014) and Rifkin (2012).